Sandow and Pilates

Posted on February 27, 2020 by Movement Health in Physical Culture, Pilates

When you explore the Physical Culture Movement of the late 1800’s-early 1900’s you can start to develop a picture of some of Joseph Pilates influences. One influence of particular interest is Strongman Physical Culturist Eugen Sandow.

Eugen Sandow (1867-1925)

Born Friedreich Müller in Konigsburg, Prussia (Germany) in 1867, Sandow is considered the, ‘Father of modern Bodybuilding’. As a child he developed an interest in exercise via the Turnen gymnastic movement (learn more here) (Morais, 2013) and as a young adult was taught weightlifting by ‘Professor Attila’ at his gymnasium in Brussels (Chapman, 1993). By 1887 Sandow was travelling Europe as a wrestler (Morais, 2013) and his big break came in London in 1889 where as a 21 year old he beat French Strongman (learn more here) performer, Sampson who promoted himself as the ‘Strongest man on earth’. During his music hall shows Sampson would invite people from the audience to see if they could match his feats of strength; Sandow was in attendance at one of these shows and accepted Sampson’s challenge. Sandow ended up beating the performer in a series of challenges that included iron bar bending, chaining breaking and the lifting of heavy objects (Chapman, 1993).

After this performance Sandow’s celebrity began to grow and he was in high demand himself as a music hall performer. To help negotiate this new found success Sandow took on a promoter named Florenz Zigfield and fairly quickly they realised audiences were more interested in Sandow’s muscles than his acts-of-strength. This resulted in the choreographing of shows where Sandow would muscle pose in costumes that had been prepared to look like Ancient Greek and Roman sculpture (see below) (Drane, 2015).

Joseph Pilates (1883-1967)

Joseph Pilates (1883-1967)

Joseph Hubertus Pilates was born in Mönchengladbach, Germany in 1883 and is the creator of the Physical Culture system called Contrology (later to be called the Pilates method). As a child he was also exposed to the Turnen gymnastic system and as a young adult developed an interest in health, exercise and the sport of Boxing. In 1914 he left Germany for England and when World War One started he was interned because of his German heritage. Whilst interned Pilates ran exercise classes for the fellow interns and it is likely this was when he began to integrate his exercise experiences into creation of Contrology (Rincke, 2019). During internment Pilates also met lifelong friend August Benkert. As a part of their research for the book titled ‘Hubertus Joseph Pilates The Biography’, authors Pont and Romero (2013) interviewed Mr Benkert and he states that his and Pilates friendship developed because of shared admiration for Sandow.

A big part of the Pilates folklore is his early formative experience working in music halls performing as a living Greek statue. There is little evidence to corroborate the story; however it’s possible this could have happened in the months between his arrival in England in the early parts of 1914 and before his internment in August, 1914 (Pont & Romero, 2013). The similarity between Pilates and Sandow’s experience as performers is uncanny.

The Grecian ideal

With his popularity as a performer on the rise Sandow’s commitment to the ‘Grecian Ideal’ became a large part of his mystique. Sandow believed the perfect physique could be found in Ancient Greek sculpture and set about studying the ancient gymnasium and its training methods. It’s said he would visit museums and measure the physical proportions of the Ancient Greek statues, then commit to emulating them via his own training (Drane, 2015).

Also around this time, the first modern Olympic Games were held in Athens in 1896 and this served to create an interest in Ancient Greece among the broader population (Pont & Romero, 2013).

It would seem Pilates was equally enamoured with the Ancient Greeks when he writes in his book titled, ‘Your Health’ (1934):

“The mode of living prevalent amongst the ancient Greeks was, of course entirely different from that of today. These people were nature-lovers. They preferred to commune with the very elements of nature itself – the woods, the streams, the rivers, the winds and the sea. All these were natural music, poems and dramas to these Greeks who were so fond of outdoor life.” (p.38).

“Were we to discontinue much of our present mode of living and discard our present systems of physical training, and instead, adopt such training as I here advocate, based upon the science of “Contrology” there would result a rejuvenation of mind and body and living itself would again become an art as it was in the days of the ancient Grecians.” (p.39).

Sandow the entrepreneur

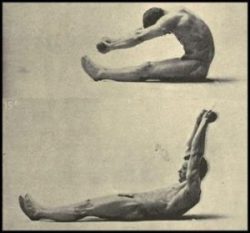

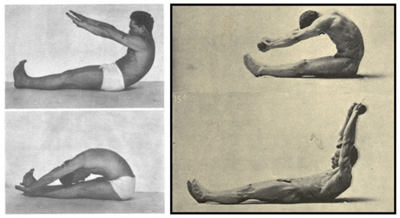

Very quickly Sandow began to leverage his popularity as a performer in to the marketing of books about Physical Culture (Morais, 2013). In 1894 Sandow published his first book titled, ‘Sandow on Physical Training: A Study in the Perfect Type of the Human Form’, below on the right is an image taken from that book. On the left is an image taken from Pilates book published in 1945 titled, ‘Return to Life Through Contrology’.

Pilates (1945) and Sandow (1894)

Pilates (1945) and Sandow (1894)

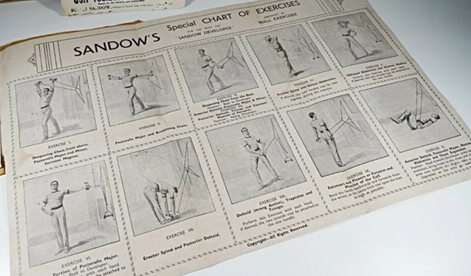

The next book Sandow published was called, ‘Strength and How to Obtain It’ (1897) and in this book he introduced the ‘Developer’. This was a piece of home exercise equipment that consisted of long bands with handles that could be fixed to a door. A copy of the Developers instruction booklet is shown below and quite a few of the exercises resemble exercises that are performed using arm springs on the Pilates Cadillac apparatus.

Sandow’s Developer (1897)

Sandow’s Developer (1897)

Whilst continuing to perform in music halls and vaudeville, Sandow’s entrepreneurial endeavours expanded further in 1897 when he established the Curative Institute for Physical Culture in London. Men and women could attend the institute and learn Sandow’s methods in the use of dumbbells. The institute also provided dietary guidance and promoted their services as being able to help people with conditions such as insomnia, nervousness and constipation. Such was the popularity of the institute a further two were opened in London and one also in Manchester, Liverpool and Boston (USA) (Morais, 2013). A lot of the people who attended the Curative Institutes were men who were practicing Muscular Christianity which was a popular Physical Culture practice at the time (Drane, 2015).

Sandow’s entrepreneurial expansion continued in 1898 and involved publication of a magazine called ‘Sandow’s Magazine of Physical Culture’. The magazine was fairly ‘populist’ in tone and served to further position the Sandow name as one that was synonymous with strength and health. The magazine ran until 1907 and provided another outlet for Sandow to promote home exercise products (Morais, 2013). Two of these products are shown below and interestingly it looks like Sandow had started to use springs as a form of resistance.

Sandow’s Developer (1907) and Spring grip barbell (1906)

Sandow’s Developer (1907) and Spring grip barbell (1906)

Sandow had now established himself as a brand and in 1901 he used this to organise a muscle posing competition to find the United Kingdom’s best developed man (Morais, 2013). This is considered to be the first ever Bodybuilding competition and is why Sandow is known as the ‘Father of modern Bodybuilding’ (Drane, 2015).

From 1889 through to the early 1900’s Sandow was a significant presence in European popular culture. In 1903, he was known as the worlds highest paid vaudeville performer and toured extensively promoting his brand and associated products; between 1902 and 1919 he publish four more books with titles such as, ‘Life is Movement’ (Morais, 2013). Pilates was born in 1883 and would have been 21 years old when the German version of, ‘Strength and How to Obtain It’ was published in 1904 (Rincke, 2019). As a young man interested in gymnastics and boxing, it would have been highly unlikely that Pilates was not exposed to some of Sandow’s work. And when you look at some of the exercises used by Sandow and the pieces of equipment he created a picture can start to emerge around some of Pilates early influences.

Sandow and Pilates

When you look at Sandow’s life he was a global celebrity, in a time when intercontinental travel was not easy he travelled to Europe, USA, South Africa, India, Japan, Australia and New Zealand to perform. In a modern day context you could compare him to Serena Williams or David Beckham; all three started out with exceptional athletic abilities and then turned their name in to a brand that could be used to sell products to their fans and the broader public (Morais, 2013). The Sandow name was so big that in 1894 some of the world’s first moving pictures (film) were taken of him muscle posing (Drane, 2015) and in 1911 he was titled by King George V as his personal ‘Professor of Scientific and Physical Culture’ (Crompton, 2011). With a presence this great at a time that could be described as Pilates formative years it is difficult to believe that he wasn’t in some way influenced by Sandow.

Pilates system of Contrology was influenced by the Physical Culture Movement of the late 1800’s-early 1900’s (Pont & Romero, 2013; Rincke, 2019) and Sandow was a large presence in Strongman Physical Culture (Drane, 2015). When you look at some of Sandow’s ideas, exercises and products there is some similarity with the ideas, exercises and apparatus that Pilates used in the development of Contrology. However none of these observations directly connect Pilates and Sandow. There are only two direct observations connecting Pilates and Sandow that I can find. The first involves the interview with Mr Benkert that takes place as a part of Pont and Romero’s Pilates biography (2013) where he states that his and Pilates friendship developed because of shared admiration for Sandow. The second involves Rincke’s Pilates biography (2019) where she describes Pilates collaborating with Professor Dr Wilhelm Kotzenberg and that the two had a mutual enthusiasm for Sandow and weight training.

Thanks for reading, Warwick..

Chapman, D. (1993). SANDOW’S FIRST TRIUMPH Excerpted from, Sandow the Magnificent: Eugen Sandow and the Beginnings of Bodybuilding (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1994). Iron Game History 3(3), 3-9.

Crompton, C. (2011). Eugen Sandow (1867—1925). Victorian Review 37(1), 37-41.

Drane, R. (2015). EUGEN SANDOW’S BODY WAS ALL HIS OWN WORK. Inside Sport. Retrieved 21st December, 2017 from: https://www.insidesport.com.au/more-sport/news/eugen-sandows-body-was-all-his-own-work–422597

Morais, D. (2013). Branding Iron: Eugen Sandow’s “Modern” Marketing Strategies, 1887-1925. Journal of Sport History 40(2), 193-214.

Pilates, J.H. & Miller, W.J. (1945). Pilates’ Return to Life Through Contrology – A Pilates’ Primer: The Millennium Edition. Ashland, OR: Presentation Dynamics.

Pilates, J.H. (1934). Your Health. Ashland, OR: Presentation Dynamics.

Pont, J.P. & Romero, E.A. (2013). Hubertus Joseph Pilates The Biography. Spain: HakaBooks.

Rincke, E. (2019). Joseph Pilates A Biography. Highstown, NJ: Inner Strength Publishing.

Sandow, E. (1894). Sandow on Physical Training: A Study in the Perfect Type of the Human Form. New York, NY: J. Selwin Tait & Sons.

Sandow, E. (1897). Strength and How To Obtain It. London, UK: Gale & Polden LTD